Reinterpretation of literary sources and iconographic documentation

Even if the literary sources lack data and do not allow us to frame the site in a precise port typology, they give some indirect clues on maritime topography that can be reconsidered in the light of the geomorphologic components of the coastal landscape. Thucydides (VI, 72) reports that «...Athenians passed with the fleet to Nasso and Catania...» but never referring to the word “port”; Diodorus of Sicily (XIV, 61, 4), about four centuries after Thucydides, reminds a "Aighialòs tōn Katanáiōn" (Castagnino, 1994), that is a sandy shore. Diodorus of Sicily, in particular, emphasizes that during the second Punic war, because of a sudden storm, the Carthaginian general Imilcon had to land the ships in Catania, where the Carthaginian general Mago was waiting him with its fleet (XIV, 59; XIV, 61,4). In another passage, Diodorus of Sicily (XIV, 60, 6-7), reports that after the battle the Carthaginian anchored in Catania their triremis, without specifying if they sheltered in a harbour. Diodorus of Sicily uses the verb "hormízō" that, in strictu sensu, means “to anchor” and it doesn't implicate neither the concept of harbour nor the possibility of assuring the ship to berth bollards. It is worth noting that, even though he was telling not contemporary events, he never used the term “port”. The reinterpretation of these literary sources would suggest a coastal morphology characterized by a sandy shore, suitable for beaching military ships according to an established practice of ancient sailing. Moreover, it is evident the lacking of a real military harbour armed with arsenals, benches, docks and endowed with the necessary structures of logistic support for a fleet.

Strabo (VI, 3,19) provides another interesting topographic information. Dealing with the eastern Sicily towns, he remembers that «...several rivers, descending from Mt. Etna, flow into the sea and form easy ports at their mouths» (Ambrosoli, 1833). Moreover, this geographer considers Catania one of the most important coastal sites, and points out that it is crossed by the Amenano river (Strabo, V, 3,13), whose mouth is located south of the town. It is worth noting the accuracy of his observation that, realizing the economic importance of the combination “land-river” in the Roman colony's financial system, obviously underlines the presence of the Amenano river. In fact, under the emperor Augustus, Catania was considered caput rei frumentariae (Cicero, Verr., II, 3, 83) and the development of an important wheat market is confirmed by an epigraph (CIL XIV, 364; Manganaro, 1988) that tells the patronus C. Granius Maturus, pertaining to the guild of fabri navales operating simultaneously in the two commercial centres of Ostia and Catania. Another important literary sources (Cicero, Verr., II, 3, 83) reports that the ships arriving or transiting at Catania had to pay the city a vicesima portorii, a kind of customs duty ad valorem, equal to the 5% of the estimated value of the load. In this context, a fragmentary inscription, treating of administrative customs, refers to the coordination of the portorium carried out by an imperial procurator who provided the monitoring of conductores for tax collection (Manganaro, 1988).

Another important fragmentary epigraph, found nearby the nowadays Catania fish market and reconstructed by Manganaro (1959), adds important information to the limited but significant technical data drawn from literary sources. This epigraph reports the occurrence of ancient harbour structures that needed to be consolidated as they were damaged by storm (procella). Reference to pier (moles) and to the construction technique in opus pilarum (pila pa[cta...]) (piers connected by arches, see Fig. 8) would suggest the occurrence of a system of defence and, at the same time, of service to a small commercial harbour area. The reference to the destructive action of a storm allows us to interpret the pier as an external protection work, exposed to dominant winds, needing an emergency in order to ensure a safe shelter to ships (navigis adpulsis scabro litori). Moreover, the same inscription reports a meatus urbis referring to works of water canalization in the city with suitable drainage technique. The parallel reference to moles and meatus urbis suggests a temporal correlation in the realization of the two works, that were strategic and functional for the restoration and reorganization of the harbour area, which became necessary in consequence of both destruction of the external pier by marine storms and flooding of the city. Both structures were probably gravitating around of the lower sector of the town (the Platea Magna area, the present Piazza Duomo, Fig. 1e). In fact, the epigraph suggests that works of water canalization should have occurred in the city, probably where the mouth of the Amenano river was located (see previous chapter). In this depressed sector, flooding events and accumulation of fluvial coastal sediments could have caused the silting up of a lagoon previously used as internal harbour. During the Roman colonization, it was filled by sediments and reclaimed, the water canalized in order to feed thermal baths (e.g. Terme dell’Indirizzo, Terme Achilleane, Fig. 6) and fountains. These latter are clearly documented in the ante-1669 iconographic and cartographic documentation (Fig. 4) and are still visible in the Piazza Duomo area, such as the Amenano and Sette Canali fountains, or were buried by the 1669 lava flow and successively excavated (e.g. young hostel in Piazza Currò, Pozzo di Gammazita, Figs. 1f and 2). The age of the first building stage of the thermal baths (3rd century A.D.) help us to frame chronologically the natural event. This represents a terminus ante quem also for the restoration of the harbour pier mentioned by the discussed epigraph whose location, while precisely unknown, probably reflect a sheltering system for the harbour entrance.

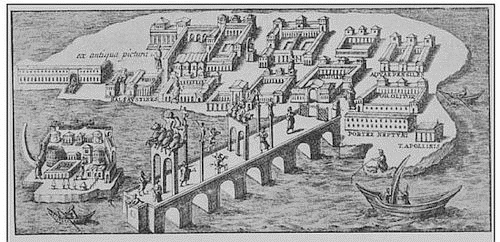

Figure 8. Arched pier of Roman Puteoli

The arched pier of Roman Puteoli (from Dvorak and Mastrolorenzo, 1991), labelled "from a Roman picture after Bellori" in reference to Fragmenta vestigii veteris Romae by J.P. Bellori (1615-1696).

The analysis of coastal morphology with respect to the prevailing wind directions (from the east: Sirocco and Levant) allow us to infer the location of the Roman pier in the Larmisi lava flow, eastern-facing the homonymous promontory (Fig. 5b). This location is suggested by the need of sheltering from the Sirocco and Levant storms the bay occurring between the Larmisi promontory and the Plaia beach. In this bay the mouth of the Amenano river and/or of the canal system reclaiming the most depressed sector of the town was located. This setting is confirmed by the drawing of N. Van Aelst (ordered by the nobleman A. Stizia in 1592 A.D.), one of the oldest view of Catania (Fig. 4c), a bird’s-eye-view that shows the urban plan of the town along the Ionian coast and Mt. Etna volcano in the background. In this view, a small pier is showed, located in the most functional position in order to shelter the southern coastal sector of the city, the most suitable to accommodate a port, from the prevailing meteo-marine agents.

The interpretation of the iconographic and cartographic documentation earlier than the 1669 eruptive event (see also Pagnano, 1992), that deeply modified the coastal morphology, provides some evidence concerning the Middle age harbour structures and the primary morphology of the beach occurring at the foot of the low hill dominated by the Swabian castle (the Ursino Castle). A shore extending from the Piazza Duomo area to the south is clearly represented in the map drawn by F. Negro in 1637 A.D. (Fig. 4b) and in the bird’s-eye-view drawn by N. Van Aelst in 1592 A.D. (Fig. 4c). The most complete and picturesque bird’s-eye-view of Catania and Mt. Etna was drawn by T. Spannocchi in 1578 (Fig. 4a). In particular, in the 10th table of the Description de las Marinas de todo el Reino de Sicilia del Cavallero Tribucio Spanoqui, the castle, presently located about 1 km on-land, appears positioned along a wide sandy beach. This fortified square structure, built according to the Swabian military standard, was conveniently located by the emperor Frederick the Second on the shore, in a position that dominated the most strategic points of the town, in order to defend it against attacks from the sea. In particular, in the Spannocchi’s view the Ursino Castle seems to be built on a small terrace at the top of a low hill dominating the sea and parallel to the coastline below. This latter is characterized by a wide sandy beach (later covered by the 1669 lava flow), that appears to be in continuity with the present Plaia beach. In the written text accompanying the Spannocchi’s view, it is clearly affirmed that in 1578 A.D. Catania «...do not have a harbour nor a shelter for ships …». This lack is evident also in the accurate 1637 A.D. Negro’s map (Fig. 4b) that reports the word “porto” in correspondence of the narrow inlet, visible also in the Spannocchi’s view, located east of the cathedral where opened the gate “del Porticello” (or “Porta Vega”) in the 16th century fortifications (Fig. 1e). On the contrary, the 1592 Van Aelst’s view (Fig. 4c), portrays a small pier placed right in of the same inlet called «portus», where ships are not docked. Here, the ships appears far moored in a dispersed manner in the bay between the basaltic Larmisi headland and the beach below the Ursino Castle.

Another important iconographic source is represented by the giant wall fresco, entitled “Catania during the 1669 eruption”, realized in 1679 A.D. in the Catania Cathedral and attributed to the painter Giacinto Platania (Fig. 4d). With images very efficacious and rich in evocative details, the artist manages to visually communicate the violence of the lava burying the beach adjacent to the Ursino Castle, as far as the bastions of the castle, and completely changing the primary morphology of the coastline. Even here we note the presence of a small pier in front of the gate “del Porticello” on which many citizens are waiting in line to escape by sea to the disaster. In order to understand the morphological change of the coastline caused by the 1669 lava flow in the southern sector of the town, it is very useful to compare Figs. 4b and 4e.

The analysed cartographic and iconographic documentation allow us to reconstruct the morphologic changes of the beach, now obliterated by the 1669 lava flow and urban works, that stretched from the Larmisi basaltic cliff to the south (see also D’Arrigo, 1929). It’s worth noting that in 1578 A.D. the city was not equipped with a port at the mouth of the Amenano river, in the northernmost sector of the beach. The comparison between the descriptions of Spannocchi (1578, Fig. 4a) and Negro (1637, Fig. 4b), on the one hand, and the descriptions of Van Aelst (1592, Fig. 4c) and Platania (1679, Fig. 4d), on the other hand, also suggests that during the period between 1578 and 1669, this bay was alternatively sheltered by a small pier. The analysis of literary sources, iconographic documentation and meteo-marine data, suggests that the pier could have been located in the same position of the pier in opus pilarum used during the Roman colonization and that was restored in the Late Roman period (Fig. 5b). As a matter of fact, for its exposure to the devastating storms from the east, this harbour structure went through several stages of destruction (Fig. 5c) and reconstruction, as documented by the Late Roman epigraph (see above). After the 1669 eruptive event, and the consequent formation of a deep and small bay north of the lava flow (Fig. 5d), this coastal stretch underwent abundant coastal-alluvial deposition (Fig. 5e) and was later incorporated into the urban transformation (Fig. 5f).