Archaeological data

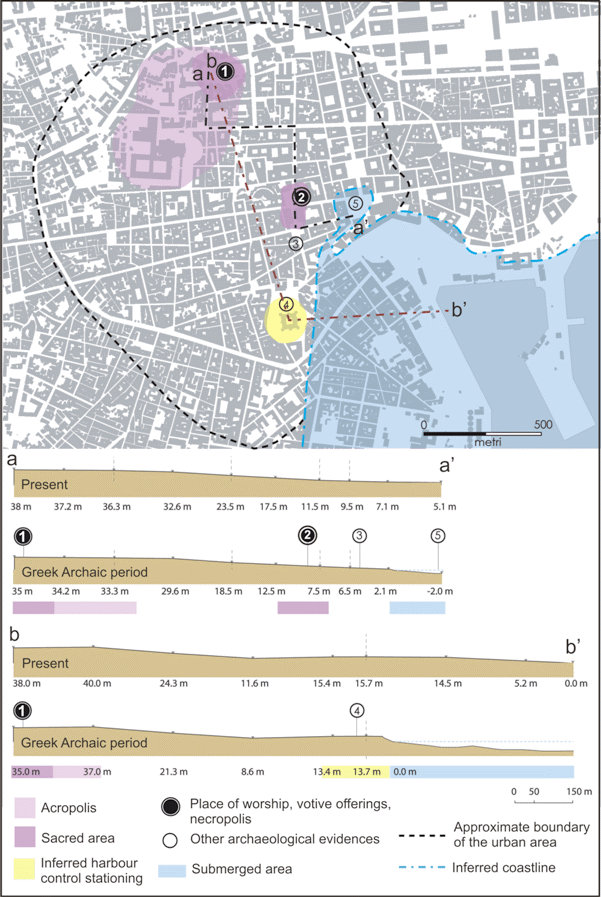

To the current state of researches (see also Castagnino Berlinghieri and Monaco, 2008), at least two distinct components seem to characterise the harbour area of the colony Katane during the Greek period (Fig. 9): downtown, on the top of a morphological terrace (the present Ursino Castle area at 15 m a.s.l.), there was a stronghold of control overlooking the sea; in the area of the present Piazza S. Francesco d'Assisi votive offerings were located, belonging to a feasible coastal sanctuary that was closely connected to the port system. Uptown, on the top of higher morphological terrace (the Montevergine hill), the Greek acropolis and the early urban compound (a sort of primary form of urban organization) are attested by archaeological evidence dated to the 6th century B.C. (Frasca, 2000). The east-west oriented wall discovered within the Ursino Castle, associate with proto-Archaic Greek pottery shreds (Patanè, 1993-1994), suggest that this area was regularly used by Greek colonists since the 8th century BC. In particular, the remains of these masonry structures underline the importance of the strategic stronghold place in a coastal dominant position with specific control functions, most likely related to defence and security of the harbour (Fig. 9). These data confirm the possible occurrence of an inner natural harbour located in the present Piazza Duomo area at the mouth of the Amenano river (Fig. 5a), used as a landing place by the first Greek settlers who founded Katane in the 8th century B.C. Successively, during the entire Greek period, it was also exploited as a transit area for maritime trade. As a matter of fact, the meaningful votive offerings discovered in Piazza San Francesco (ex voto in ceramics, belonging to various typologies) are witness of long-routes trade relationships with central and eastern Mediterranean since the Greek Archaic period.

The vestiges of “taluni avanzi di arte antica” (some remains of ancient art) identified by Sciuto Patti (1896) in Via Zappalà Gemelli (Fig. 9), that appears located along the western edge of the hypothesised harbour area, were probably built as foundation for the construction of an upper platform, probably conceived in connection with the nearby Piazza San Francesco votive offerings area, as part of a feasible coastal sanctuary (see discussion in Castagnino Berlinghieri and Monaco, 2008). To the south, the coastline located at the bottom of the Ursino Castle (buried by the 1669 lava flow) appears as the same stretch of sandy beach referred by Thucidides (III, 116), that was probably used as a military base of Athens within the Athenians and his allies naval manoeuvres against Syracuse during the War of the Peloponnesus in the 5th century BC. Literary sources also suggest that a sandy beach, the "Aighialòs tōn Katanáiōn" (Diod. XIV, 61, 4), was still used as a military base during the Second Punic War. As regards the coastline north of Piazza Duomo, we can assume that the coastal morphology at the time of the Greek colonization should have been very similar to the present (see Geological data). The two bays of Guardia and Ognina (Fig. 2) were only partially invaded by small branches of the 1381 lava flow. Literary sources also suggest that this coastal stretch may have hosted a small port, which was not directly connected with the urban centre of Catania being placed to the north (see also Tortorici, 2002), probably in the so-called Porto Ulisse at the bay of Ognina (Castagnino, 1994).

After the Roman conquest of the city in 263 B.C., Catania became a “Roman colony” under Augustus in 21 B.C. In that period the harbour area was gradually involved in an intense period of upgrading of the entire city, from the Montevergine hill to the downtown, that was improved until the 3rd century A.D. Natural transformations probably occurred at the mouth of the Amenano river and in the inner harbour area, that was subjected to silting process. It resulted from the combination of fluvial-coastal sedimentation along with sea-levels rising and tectonic uplifting. A comparison between the river harbours of Ostia and Catania could be very useful in order to understand how technical challenges and risks related to the infilling phenomena can be approached differently. As regards the Ostia harbour, located at the mouth of the Tiber river, the silting problem was solved in a radical way by abandoning the port itself in order to build another one, much safer and more convenient than the river harbour, in a place a few kilometres to the north. In the Catania harbour area, conversely, the water flowing on the surface was canalized in a system of underground canals, also in order to gain ground on the sea. The meatus urbis (works of water canalization), mentioned in the marble epigraph (Manganaro, 1959), seems to refer to this sector of the city. Along with the development of maritime infrastructures to better support the inner harbour, dating from the mid-Republican age to the first-Imperial age, considerable clean-up operation of the port took place from mid-3rd century A.D. Mostly, the Piazza Duomo area was reclaimed and the water fed at least two thermal baths (Terme Achilleane, Terme dell’Indirizzo). At this stage seems to be dated the building of an outer defence system, made in opus pilarum (piers connected by arches), in order to broaden the harbour area (Fig. 5b).

Figure 9. Main Greek Archaic features in Catania

Location of the main Greek Archaic features in Catania (from Castagnino Berlinghieri and Monaco, in press); (1) ex Reclusorio della Purità; (2) Piazza San Francesco; (3) Via Zappalà Gemelli; (4) Ursino Castle; (5) ancient harbour (hypothesis). The sections below illustrate the change of the topographic elevation (a.s.l.) from the Greek archaic period to the present. For the reconstruction of the old elevation, we subtracted from the present elevation 3 m, obtained by the vertical tectonic uplift (about 5 m, considering an uplift rate of 2 mm/yr) minus the sea level rise (about 2 m in the last 2500 years). Moreover, we subtracted from the present elevation also the thickness of remains of anthropogenic origin and of the 1669 lava flow (only in the B-B’ section) obtained by bore-holes (see Monaco et al., 2000).

If we assume that in Roman times the harbour was equipped with port-related structures, such as moles, quays and warehouses for storage of goods, the fifteen east-west oriented parallel walls discovered (Sciuto Patti, 1856) in old excavations under the Palazzo del Duca Tremestieri, located in Via Lincoln (nowadays Via Sangiuliano, 300 m north of Piazza Duomo), could be referred to maritime infrastructure to store merchandise. Even though we have an incomplete picture of these ruins, because at the time not properly documented, they clearly show the presence of a large complex, which consists of long rectangular rooms as part of a whole project that works on the repetition of equivalent forms, with a plan reminding the arrangement of the Roman horrea (Staccioli, 1962). This is confirmed by the discovery of in situ part of columns and mosaics. This would suggest that this plan of walls was provided by an open central area preceded by a colonnade, as for example in Horrea I, VIII, 2 of Ostia. The design aspects, together with its location close to the road network of the Imperial age documented in Via Crociferi, allow us to evaluate its possible chronological correlation within the urban-planning system right along the main road leading to the port. Similarly to other sites characterized by river harbours, we can also identify a control tower for maritime and commercial harbour activities in the rectangular structure identified in old excavations (Musumeci, 1819; Ferrara, 1829; Gemmellaro 1852) along the ancient Via del Corso (nowadays Via Vittorio Emanuele, near Piazza Duomo). This structure can be interpreted as the basement of a “lookout tower”, similar to that occurring in the Ostia river harbour (Calza et al., 1953), rather than as the “remains of the triumphal arch of Marcello” (see Rizza, 1981, 28-29, 41-42) or the "podium of a worship building dated to proto-imperial period" (see Buscemi, 2006, p. 159, note 13).