Rotation of units around the Manning and Hastings oroclines

Curvature of the western arc

Despite the absence of the western arc due to inferred underthrusting, the distribution of “proximal” Carboniferous volcanic fields in the Tamworth belt outlines a curvilinear shape to the present, largely faulted inner margin of the forearc basin between Muswellbrook in the north and Port Stephens in the southeast (Fig. 1b). Offshore extensions of Carboniferous volcanic rocks extend south of Sydney, indicating that the approximate arc/forearc basin boundary outlines an open, anticlockwise fold pair (Fig. 1b). Proximal Carboniferous volcanic rocks are absent from the Hastings Block (Roberts et al. 1995).

Rotation of the boundary between forearc basin and its basement and the subduction complex.

Figure 1b shows that over most of the southern New England Orogen, subduction complex rocks lie east of forearc basin sediments. That means that the vector towards the trench points east. In the hinge of the Manning orocline, however, subduction complex rocks lie north of forearc basin sediments and the vector points north. In this hinge region, the subduction complex/forearc boundary truncates stratigraphy in the forearc basin that is controlled by NNW trending folds and faults (see below). On the western side of the Hasting block, subduction complex rocks lie west of forearc basin sediments and the vector points west or southwest, despite being largely obscured by overlying early Permian strata (see below). In the southeastern part of the Hastings Block a fault slice of Devonian strata (Touchwood Formation) is separated from the main part of Hastings Block by an early Permian overlap assemblage and lies in fault contact with subduction complex rocks to the east (Och et al. 2007). There, the vector points southeast again, having been folded around two major oroclinal hinges (Fig. 1b).

Devonian-Carboniferous units in the forearc basin around the Manning and Hastings oroclines

Major facies changes occur within the southern Tamworth belt and the Hastings Block, complicating correlation of geological units (Roberts et al. 1991; Roberts et al. 1995). Relations between strata of the Tamworth belt and the Hastings Block are also obscured by widespread development of both early Permian sedimentary rocks, and by Early Triassic sedimentary units that cover the southeastern part of the Hastings Block (Fig. 3). A key feature of the north Hastings Block is that in the Namurian, shallower water conditions existed in the east with deeper water in the west (Lennox and Roberts 1988). While this is the opposite of the Tamworth belt (Lennox and Roberts 1988), it is consistent with the rotation of stratigraphy around the Manning orocline and consistent also with above-mentioned rotation in direction of the trench-facing vector.

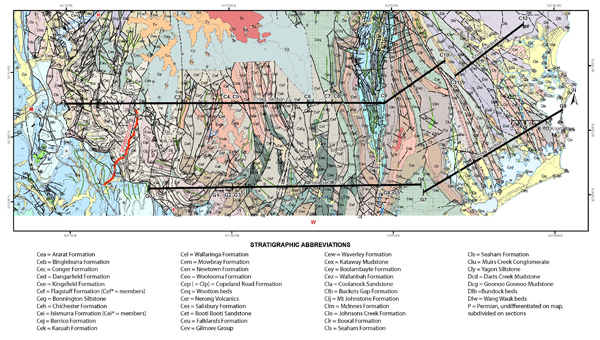

Figure 4. Simplified map of southern part of the Tamworth belt

Simplified map of southern part of the Tamworth belt. In the left corner, the folded Hunter Thrust separates blue-coloured Permian units in the southwest from coloured Carboniferous units in the northeast. The meridional Stroud-Gloucester Syncline runs though locality C9 in cross section C. The red line is seismic section DPIHM07-06; the two black lines are cross sections C and G. Short green lines are fold axial traces. Abbreviations: M=Muswellbrook; R= Rouchel; E=Elderslie; W=Woodville.

Using the time-space plot of figure 2, we have produced a map of the forearc basin (and its basement) that ignores detailed stratigraphic names, and focuses instead on time slices (Fig. 3). These are now discussed.

Basement to the forearc basin, comprising the Tamworth Group (Gamilaroi arc) and correlative units to the east. North of A (Fig. 3), the Tamworth Group occupies a SSE-trending zone in the eastern part of the forearc basin. At B, fault repetition is present (eg. Offler and Gamble 2002). A second line of Tamworth Group to the west, at C, occurs in two windows beneath Tertiary basalts and mainly represents fold repetition. From D to E, the Tamworth Group trends ENE. Possible extensions of the Tamworth Group lie south and southwest of Taree (locality F, Fig. 3). The Bitter Ground Volcanics and Birdwood Formation/Elenborough Volcanics on the western side of the Hastings Block (G Fig. 3, and Fig. 5) are also included in this time slice, with their Frasnian age indicating an age correlation with the upper part of the Tamworth Group (Roberts et al. 1995) (Fig. 5b). Aitchison et al. (1994) and Aitchison and Ireland (1995) suggested that these rocks and the underlying disrupted Yarras ophiolite (Leitch 1980) represent another fragment of the Gamilaroi arc. The Emsian Touchwood Formation and the Givetian Mile Road beds (now Formation, Pickett et al. 2009) (H) are other fragments of the forearc basement, this time on the southeastern side off the Hastings Block (Figs. 3, 5).

The lower part of the forearc basin occupies Tournasian zones 1b and 2. In the north, this time slice is broadened to include the Mandowa Mudstone, (outcropping on both limbs of a regional anticline, from west of Manilla to northeast of Wingen), and the Goonoo Goonoo Formation east and southeast of Wingen (Fig. 3). No strata of this time slice occur in the forearc basin between the Hebden area and the Stroud-Gloucester Syncline. East of the Stroud-Gloucester Syncline, this zone comprises the Darts Creek and Bundook beds that occur in N to NNW-trending fault slices (Fig. 4), interpreted to be part of an east-verging imbricate thrust stack in cross section C (Fig. 8b, c). In the Hastings Block, it includes the Pappinbarra Formation, the lower part of the Hyndmans Creek Formation and the lower half of the Boonanghi beds (Fig. 5).

The middle part of the forearc basin, occupying Visean zones 1 and 2, contains the lower part of the Merlewood Formation (in the north) and the lower part of the Isismurra Formation, which can be tracked as dipping and repeated ignimbritic strata from just north of Muswellbrook to just west of the Cranky Corner Basin (Fig. 4). Farther east, this time slice includes the Flagstaff Formation, Bonnington Siltstone, and upper Wootton beds on the west side of the Stroud-Gloucester Syncline and the Boolambayte Formation on the east (Fig. 4). In the Hastings block, it is represented by the upper part of the Hyndmans Creek Formation and the upper half of the Boonanghi beds (Fig. 5).

the upper part of the forearc basin occupies the Namurian stage. It includes the lower half of the Seaham Formation (Figs. 3, 4), that can be tracked in synclines from Wingen to Muswellbrook, as dipping strata in the immediate hangingwall of the Hunter Thrust south to Hebden, and as isolated doubly plunging synclines south to Woodville (Fig. 4). Its easternmost extent is a linear zone on the western side of the Myall Syncline. To the east and north, it is replaced stratigraphically mainly by the Booral Formation on the western side of the Stroud-Gloucester Syncline, and then by the Yagon Siltstone farther east: both occur in fanning fault slices that lie at high angles to the forearc basin/subduction complex boundary (Fig. 3). In the Hastings Block, it is represented by the Mingaletta, Majors Creek and most of the Kullatine and Youdale C formations that clearly outline the Parrabel Anticline (Fig. 5).

Curvature of early Permian units

Early Permian units with SSE-oriented outcrop boundaries overlie subduction complex rocks just east of the Peel-Manning Fault System, north and northwest of locality E (Fig. 3). Between E and G, the trends of these outliers change from SSE to NNE, outlining a north-plunging synform in the east that overlies the forearc basin/subduction complex boundary. Between G and H (Fig. 3), shallow-water early Permian strata have been folded around the Hastings Block, separated from underlying Late Carboniferous strata by a disconformity or unconformity (Roberts et al. 1995).