Introduction

As many other cities of art, Naples and its surrounding areas show a strong connection between field geology and architecture. Rocks outcropping in the area were widely used for building purposes so that a sort of specific local “urban colouring” can be recognized as a function of the geomaterials used in the construction of buildings and monuments. Just like the white of travertine for Rome, the grey of the so-called “pietra serena” for Florence and the red of bricks made of local clays for Siena, the dark grey colour of Piperno (usually combined with the yellow of the Neapolitan Yellow Tuff) gave an unmistakable imprint not just to the city of Naples but also to its neigbours of Pozzuoli, Aversa and Portici.

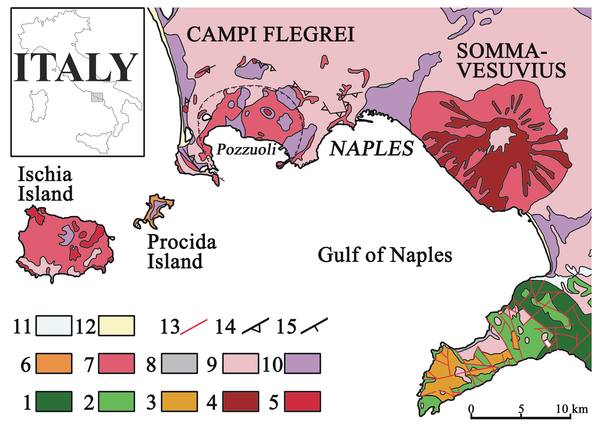

Figure 1. Geology of the Neapolitan area.

Geological sketch map of the Campanian area with the location of the Campi Flegrei and the Somma-Vesuvius districts [modified from Bonardi et al. (1988)]. 1) Lower Cretaceous-Liassic carbonate platform deposits; 2) Upper Cretaceous rudistic limestones; 3) Serravallian-Upper Langhian pre- to late orogenic silicoclastic and carbonatic deposits; 4) ultrapotassic lavas (leucitic-basanite and leucititic series); 5) potassic lavas (shoshonitic series); 6) hyalotuffs; 7) pyroclastic flows and surges; 8) Campanian Ignimbrite pyroclastic deposits; 9) pyroclastic fall deposits; 10) volcano-sedimentary deposits; 11) Upper Pleistocene talus breccias; 12) Holocene beach and coastal dunes; 13) faults; 14) boundary of the CI caldera [according to Perrotta et al. (2006)]; 15) boundary of the NYT caldera [according to Scarpati et al. (1993)].

The geological setting of the territory, along with the widespread occurrence of volcanic and pyroclastic materials in the whole Neapolitan province, strongly conditioned the architecture of Naples and the minor centres since historical times. The sources of these materials are represented by the Campi Flegrei volcanic field and the Somma-Vesuvius complex, two still active volcanic districts belonging to the so-called Plio-Pleistocene “Italian Potassic Magmatism”. In particular, the Phlegrean products, due to their abundance and their good workability, as well as their good physical and technical properties, played a significant role in the Neapolitan architecture throughout history. In fact, tuffs have been mainly exploited for the production of dimension stones and also widely used as fine aggregates mixed with pozzolana and lime for the production of the famous Roman plasters. Piperno, to a more limited extent, definitely represents the most significant building stone of the Neapolitan architecture, due to its excellent physico-mechanical features and, above all, for its typical pattern which made it the most used decorative stone between the 18th century and the World War II. Notwithstanding their limited availability, Phlegrean lavas were mainly exploited as road paving blocks and, subordinately, as architectural elements such as columns and building basal elements. Since the 18th century these two stones were progressively replaced by the Vesuvian lavas which were intensively exploited until the 1970s and 80s.

If the local geological setting has represented for Naples and the neighbouring towns a resource and a “positive” value, at the same time it can not be denied that various geohazards threaten the area: volcanic eruptions, landslides, cavity-related surface effects, all connected to the geological and geomorphologic setting. Urban settlements, in fact, rest on a subsoil made of loose and welded pyroclastic deposits, and are located, as previously stated, between the two active volcanic districts of Campi Flegrei and Somma-Vesuvius. In addition, the towns are only a few tens of km from the Apennine chain, where several seismogenetic faults are present. Minor effects can also be caused by coastal erosion, bradiseism and flood events. From a geomorphologic standpoint, the towns of the area are characterised by a hilly landscape, carved in the volcanic products cited above. Such hills, partly “conquered” by man in historical times, have been intensely urbanised since World War II, when some urban districts started to develop both at the top and at the foot of the major hills. Urban growth has increased the risk to some hazards including movement in both lithified and loose pyroclastics (falls, topples, slides, flows).

In addition, due to the good engineering properties of local geological materials (mainly the “pozzolane” and Neapolitan Yellow Tuff), the urban subsoil has been characterized by open-pit and underground quarrying activity since pre-historical times. Underground, instabilities are frequent, causing related damage to the overlying buildings and, sometimes, to humans (15 in two episodes occurred in 1996).

The aim of this paper is to give an exhaustive portrait of the several points of contact between the geological and urban settings of a heavily populated area such as Naples and its surroundings, demonstrating how the evolution of the city has been and still is so deeply and indissolubly influenced by the numerous environmental factors governing the evolution of the territory.