Tectonic setting

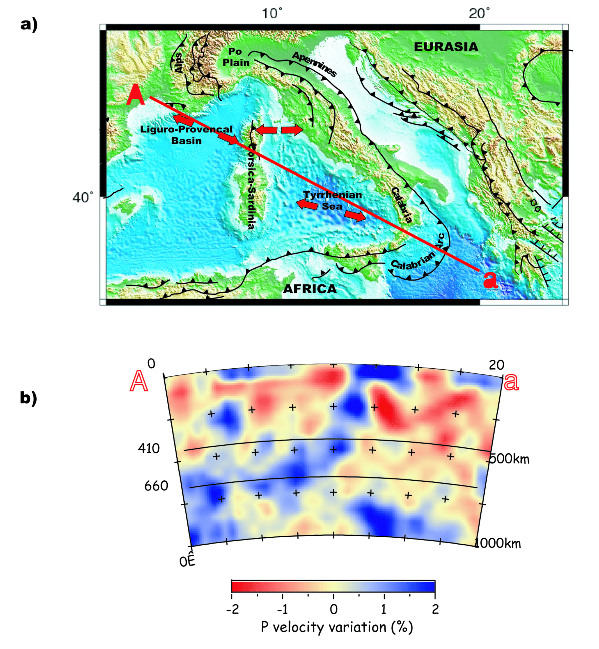

The complex lithospheric structure characterizing the Central Mediterranean is the result of long-term evolution, having as fundamental ingredient the slow convergence of the heterogeneous continental margins of Africa toward the stable Eurasia (Figures 1a, 2). This interaction, which was active over the Cenozoic at a rate of 1-2 cm/yr on average (Dewey et al. 1989, Jolivet & Faccenna 2000), consumed the former Tethys Ocean and caused the rise of the Alpine chain where continental collision occurred. From the Oligocene onwards (30 Ma), the scenario differentiated between the Apennininc and the Calabrian sectors. In the former area, the passive continental margin of Apulia entered the trench, leading to the subduction of the continental lithosphere (Dercourt et al. 1986), as proven by the inclusion of continental passive margin rocks in the Apenninic accretionary wedge (e.g., Boccaletti et al. 1971). Subduction progressively slowed, leading from an active subduction to a Rayleigh-Taylor-like instability as presently illustrated by tomographic images (see Faccenna et al. 2001b). The southern area, on the contrary, has been dominated by an impressive (>800 km; up to 6 cm yr-1) slab rollback, which is enhanced by the small, subducting, oceanic Ionian basin and, additionally, by the opening of the back-arc basins (Le Pichon 1982, Malinverno & Ryan 1986). Consequently, an extensional deformation has been locally superimposed on the sites of previous continental thickening (Horvath & Berckhermer 1982). Back-arc opening occurred in discrete episodes. The first episode of extension, occurring from 30-16 Ma (Cherchi & Montandert 1982, Burrus 1984, Gorini et al. 1994, Seranne 1999), allowed the formation of the Liguro-Provençal Basin. The extensional process was characterized by an estimated cumulative spreading/rifting of about 400 km (Burrus 1984, Chamot-Rooke et al. 1999) and was accompanied by the emplacement of volcanic, basaltic-andesitic deposits (Beccaluva et al. 1989 and references therein). At the same time, the Sardinia-Corsica block rotated counter-clockwise (van der Voo 1993, Speranza 1999). The slab should have reached a sharp bend during this phase, extending from northern Tunisia to the Apennines, probably with a tear just south of Sardinia (see Faccenna et al. 2004 for discussion). The subsequent episode of eastward extension shifted towards the Tyrrhenian domain (Carminati et al. 1998, Faccenna et al. 2001b) and started after a short, but clearly recognizable interval of about 3-5 Myr, during which extension and magmatism ceased. Two episodes of oceanic spreading occurred in the Tyrrhenian forming the following: (1) the Vavilov Basin during the Pliocene (4-3 Ma) and (2) the Marsili Basin further to the east, whose activity was restricted to approximately ~2-1 Ma (Patacca et al. 1990, Nicolosi et al. 2006) The pulsating Tyrrhenian backarc spreading has been related to the progressive shallow segmentation and deep disruption of the subducting Calabrian lithosphere (Faccenna et al. 2005, Chiarabba et al. 2008). This process is rather well documented over the region by the lateral shift of the foreland and the thrust belt activity from Tell towards Sicily (Casero & Roure 1994). It is also documented by the nature of volcanism characterized by the appearance of alkaline anorogenic products replacing the calc-alkaline products in the back-arc region (Maury et al. 2000, Faccenna et al. 2005). Currently, the Central Mediterranean subduction zone is only still active in the Calabrian sector, as indicated by seismological data. Seismicity is recorded along a narrow (~200 km) and steep (~70°) Wadati-Benioff plane, SW-NE striking and NW dipping, down to about 500 km (e.g., (Anderson & Jackson 1987, Giardini & Velona` 1991, Selvaggi & Chiarabba 1995). This view is supported by tomographic images of the Central Mediterranean mantle (Figure 1b), which reveal a continuous NW dipping high-velocity body extending below Calabria and lying horizontally in the upper-lower mantle transition zone (e.g., Spakman et al. 1993, Lucente et al. 1999, Piromallo & Morelli 2003). The Calabrian high-velocity anomaly creates a continuous arcuate structure that merges with the northern Apennines below 250 km (Piromallo & Morelli 2003). At shallower depths, a low-velocity anomaly, in the southern Apennines, disconnects the Calabria from the northern Apennines, which represents the seismological signature of a slab tear enhanced by the subduction of a heterogeneous continental margin. This condition not only led lateral subduction variability and slab tears but also triggered a complex mantle circulation.

Figure 1. Central Mediterranean geodynamic framework.

a) Topographic/bathymetric map of the Central Mediterranean region showing the position of the main structures. b) Tomographic cross sections Aa - Gulf of Lyon to Calabria -from model PM0.5 (Piromallo & Morelli 2003).

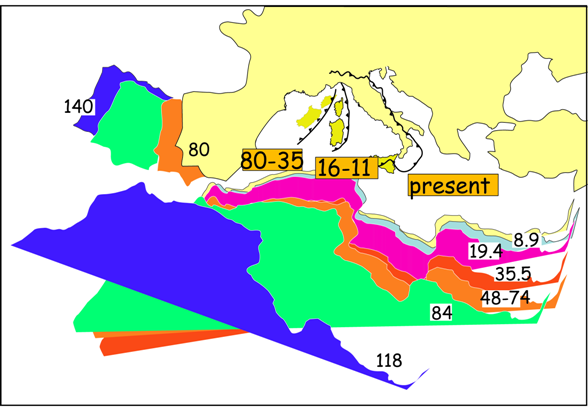

Figure 2. Motion of Africa and Iberia with respect to fixed Eurasia.

Motion of Africa and Iberia with respect to fixed Eurasia (redrawn from Dewey et al. 1989 and Olivet, 1996). The position of the Central Mediterranean trench is shown as reconstructed for the last 80 Ma (see Faccenna et al. 2001 a, b for details).

The pattern of shear wave splitting (SKS) measurements provides invaluable information to constrain mantle deformations. Civello & Margheriti (2004) showed that fast directions in peninsular Italy are quite often parallel to the strike of the thrust belt, while in the Tyrrhenian Sea, they are primarly E-W oriented, corresponding to the back-arc extensional direction. In addition, the N-S oriented measurements in western Sicily had a high angle with respect to the thrust front.