Introduction

Geological factors coupled with topographic and archaeological interdisciplinary studies on many harbours around the Mediterranean Sea, as well as the North Sea, the Baltic Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, have recently brought to light noteworthy environmental or landscape changes that have been demonstrated to be crucial for better understanding more conventional features of port archaeology. One of most stimulating topics for geo-archaeological studies, based on interdisciplinary analysis of natural and cultural formation processes, is represented by the ancient harbour system of Catania (Fig. 1a), located along the Ionian coast of Sicily (see inset in Fig. 2). This is an area prone to tectonic uplift and characterized by strong crustal seismicity (Monaco and Tortorici, 2000; Monaco et al., 2002). Moreover, the city is located on the lower southern slope of the Mt. Etna volcanic edifice, on a flight of Pleistocene coastal-fluvial terraces at the border of the Simeto river plain (Fig. 3a), and was exposed in pre-historical and historical times to repeated lava flow invasions and main flooding events. Despite the recurrence of several earthquakes and eruptions (Boschi and Guidoboni, 2001), the urban area has developed in this complex setting since the 8th century B.C., when Greek colonists from Chalkida founded Katane on the Montevergine hill (between the present Castello Ursino and Piazza Dante, see Fig. 3a).

In the history of Catania the ancient harbour system has always represented a continuous problem that generated a political debate centred around the lack, along that segment of the Ionian coast of Sicily, of a natural bay well sheltered and purposeful (D’Arrigo, 1956; Coco and Iachello, 2003). Generally speaking, we can asses that to a wealthy harbour corresponds an efficient and well-organized harbour system; this assumption cannot be applied to Catania that appears instead to be characterised by a never-ending aim toward a urban model of a “city dreaming an harbour which might keep up with his ambitions” (Aymard, 2003). Although the constant persistence of this difficulty, since the Greek Archaic period the city of Catania was closely connected with the main maritime routes linked with the Greek markets of the central Mediterranean (including the islands of the Aegean sea). This apparently flourishing condition lasted until the end of the 19th century, although the politicians were often expressing their grievances over the functional inadequacy of the harbour. Notwithstanding these problems, Catania continued to play a main role in the rising of trade and agro-export industries, especially dealing with sulphur (Barone, 1987), and several harbour-planning projects were proposed.

The diachronic reading of historic and archaeological evidence stratified in the coastal landscape of Catania shows that geomorphology or natural factors are both constant reference points for planning both urban spaces and harbour related equipment. Taking into account the new publications on Catania about archaeology (Patanè, 1993-94, Tortorici, 2002; Branciforti, 2005) as well as geo-vulcanology (Boschi and Guidoboni, 2001; Tanguy, 2007), also considering the observations already discussed by the authors (Castagnino, 1994, Monaco et al., 2000, Castagnino Berlinghieri and Monaco, 2008), this work provides a fresh interdisciplinary perspective which combines new data of each related field involved. The investigation of all of these data, which were analysed also in view of the military and commercial functional needs of the ancient city, sheds new light on few crucial questions about the ancient topography and makes it possible to project new hypotheses about the ancient waterfront and the precise functional areas of the harbour system of Catania starting from the Greck Arcaic age until the late-Roman period.

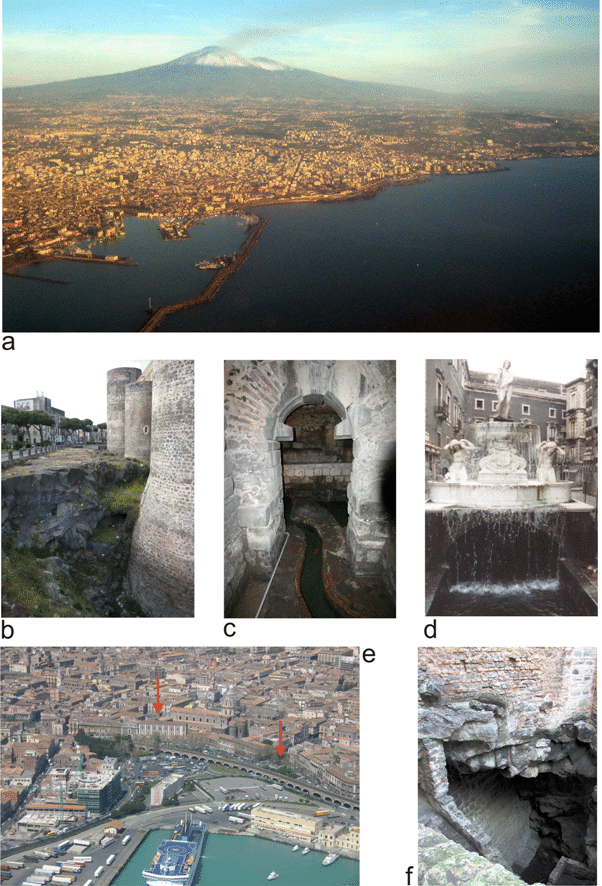

Figure 1. View of Catania and Mt. Etna

a) Aerial view of Catania and Mt. Etna in the background. b) View from the south of the western wall of the Swabian Castle (Castello Ursino, see Fig. 2 for location); the 1669 lava leaning against the wall is visible. c) Water canal in the Terme Achilleane thermal baths (see Fig. 6 for location). d) The Amenano fountain (Fontana dell’Amenano, see Fig. 6 for location). e) Aerial view of the modern harbour area of Catania; arrows show the location of Piazza Duomo (on the left) and the gate “del Porticello” on the 16th century fortifications (on the right). f) The Gammazita pit (Pozzo di Gammazita, see Fig. 2 for location); the 1669 lava leaning against the 16th century fortifications is visible.

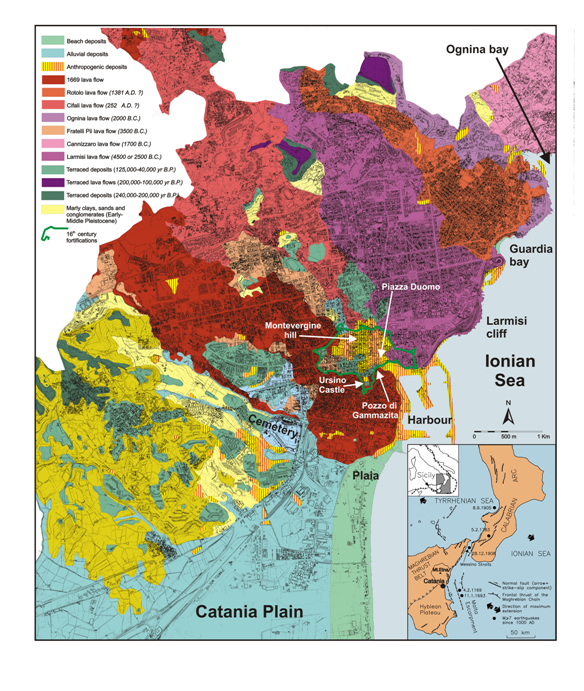

Figure 2. Geological map of central Catania

Schematic geological map of the urban area of the city of Catania (from Monaco et al., 2000, modified). Inset shows the seismotectonic features of the central Mediterranean area.

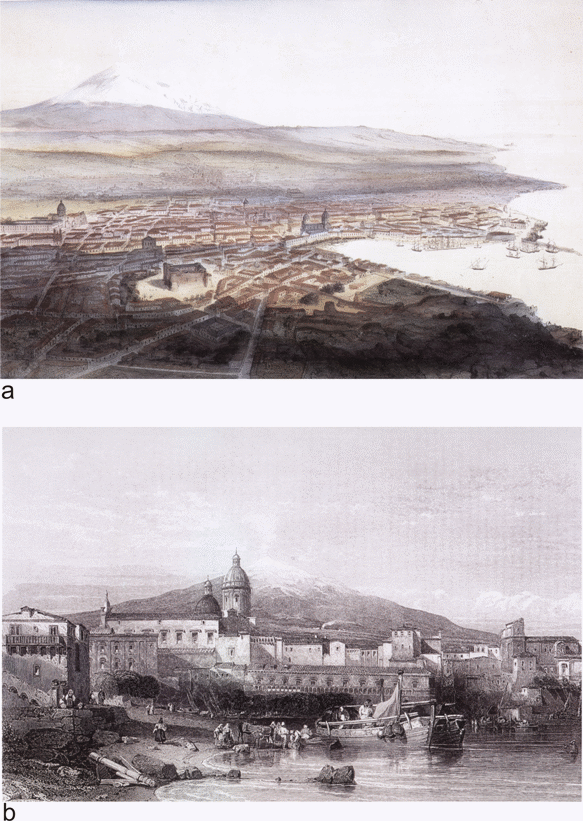

Figure 3. Catania 1849

a) Catania, view from the south-west in the coloured lithograph of Schultz (Paris, 1849). In the foreground the 1669 lava flow and the Ursino Castle are evident, to the right the harbour and the cathedral, to the left the Monastery of San Nicolò L’Arena and in the background the Mt.Etna volcanic edifice lying on a large Middle Pleistocene fluvial-coastal terrace. b) The Catania harbour and Mt. Etna in the steel engraving of W. Floyd (from Mediterranean scenery, W.L. Leitch, London, 1845). Note the front of the 1669 lava flow and the “Marina” beach on the left.