Introduction

The southern segment of the Apennine orogen (Fig. 1) represents an ideal natural laboratory to study the complex interaction between tectonic and sedimentary processes responsible for the structural architecture of a thrust belt. Furthermore, the intense hydrocarbon exploration, carried out particularly during the 1980-2000 period, made available high quality subsurface dataset (seismic reflection and well data) whereas surface geology researches provided robust structural and stratigraphic constraints. Thus, the Southern Apennines thrust belt provides a challenging mixture of high quality data and poorly documented geological features that make fruitful the scientific debate about its geodynamic setting and tectonic evolution (e.g., Mostardini and Merlini, 1986; Casero et al., 1988; Cello et al., 1989; Patacca and Scandone, 1989; Roure et al., 1991; Marsella et al., 1995; Doglioni et al., 1996; Lentini et al., 1996; Monaco et al., 1998; Mazzoli et al., 2000; Menardi Noguera and Rea, 2000; Patacca and Scandone, 2001; Lentini et al., 2002; Carminati et al., 2004; Catalano et al., 2004; Butler et al., 2004; Shiner et al., 2004; Turrini and Rennison, 2004; Sciamanna et al., 2004; Scrocca et al., 2005, 2007; Mazzotti et al., 2007; Patacca and Scandone, 2007a; Steckler et al., 2008)

As an example, the deep tectonic setting, although partly illuminated by geophysical derived information such as, crustal refraction and reflection surveys, shear waves attenuation, seismic tomography (e.g., Scarascia et al., 1994; Mele et al., 1997; Improta et al., 2000; De Gori et al., 2001; Mazzotti et al., 2007; Panza et al., 2007; Steckler et al., 2008 and references therein), is still a matter of scientific debate regarding mainly: i) the shortening in the accretionary prism particularly within the deepest thrust sheets in the Southern Apennines thrust belt (i.e. the Apulian carbonate platform units), and ii) the degree of involvement of the lower plate basement (i.e., the Apulian crystalline basement).

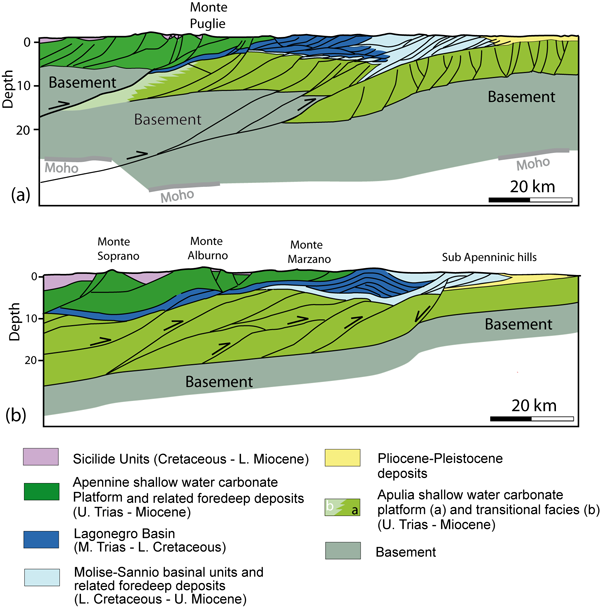

As a result, these uncertainties have produced significantly different interpretations of the Southern Apennines structure at depth deeper than 10 km, while the main tectonic features represented in published cross-sections at shallower levels are relatively similar. These different interpretations may be placed in the following two main groups (Fig. 2).

• In the first group (Fig. 2a), the possible existence of a basement wedge is suggested that corresponds to the classic backstop proposed for most of the Alpine and Cordillera types of orogen (e.g., Casero et al., 1988; Roure et al., 1991; Mazzoli et al., 2000; Menardi Noguera and Rea, 2000; Speranza and Chiappini, 2002; Sciamanna et al., 2004). The shortening within the Apulian thrust units is small, in the order of 15-25 km (e.g., Mazzoli et al., 2000; Menardi Noguera and Rea, 2000).

• In the second group (Fig. 2b), the Southern Apennines thrust belt is considered to be mostly composed of sedimentary cover while the crystalline basement remains essentially undeformed. Two different geometries have been hypothesized for the Apulian crystalline basement. In a first hypothesis, the basement dips to the west under the thrust belt, with an almost constant attitude (Mostardini and Merlini, 1986; Marsella et al., 1995; Mazzotti et al., 2000; Patacca and Scandone 2007a). In a second hypothesis the basement top follows the flexural geometry of the subducting Apulian slab (Doglioni et al., 1996; Scrocca et al., 2005 and 2007). In the thin-skinned model, shortening within the Apulian thrust units are of at least 110-120 km (e.g., Mazzotti et al., 2000).

An updated review of the structural architecture and tectonic evolution of the Southern Apennines has been carried out taking into consideration the stratigraphic and structural constraints provided by almost forty years of petroleum exploration.

The main features of the southern segment of the Apennine orogen are described and discussed on the base of a regional geological cross-section drawn nearly parallel to the CROP-04 deep seismic reflection profile (Mazzotti et al., 2000; Mazzotti et al., 2007), which traverses the entire Southern Apennines from the Tyrrhenian to the Adriatic Sea.

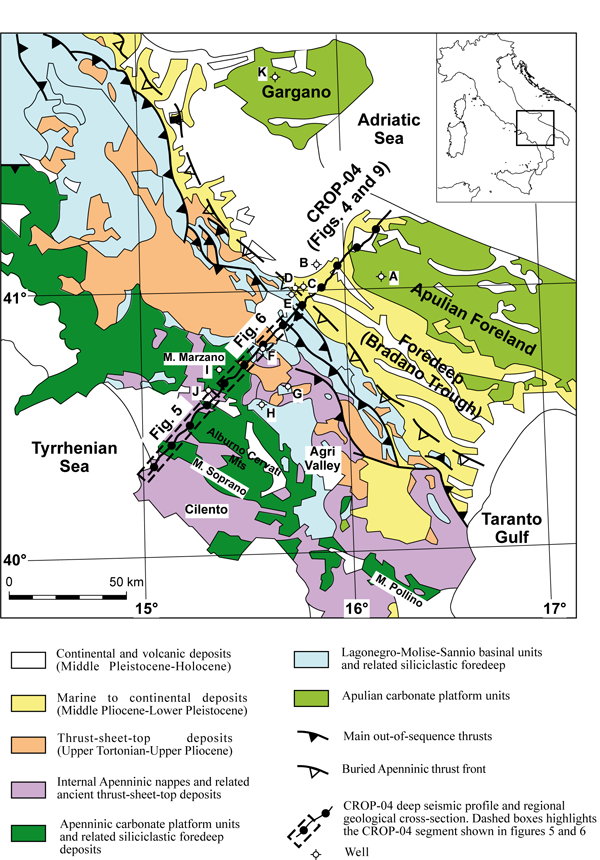

Figure 1. Simplified geological map of the Southern Apennines

Simplified geological map of the Southern Apennines (modified after Patacca et al., 1992 and Patacca and Scandone 2007). The location of the geological cross section and segments of the CROP-04 profile shown in this paper are highlighted. Letters identify relevant wells (A, Puglia 1; B, Gaudiano 1; C, Bellaveduta 1; D, Lavello 5; E, Lavello 1; F, S. Fele 1; G, M. Foi 1; H, Vallauria 1; I, S. Gregorio Magno 1; J, Contursi 1; K, Gargano 1).

Figure 2. Contrasting interpretation about the deep structural setting of the southern Apennines

Comparison between published thick- and thin-skinned interpretation of the deep structural setting of the Southern Apennines (modified after Scrocca et al., 2005). a) Thick-skinned model with the crystalline basement largely involved by thrusting and small shortening in the Apulian carbonates (modified after Menardi Noguera and Rea, 2000). b) Thin-skinned model with rootless sedimentary nappes and large shortening in the buried Apulian thrust sheets (modified after Mazzotti et al., 2000).