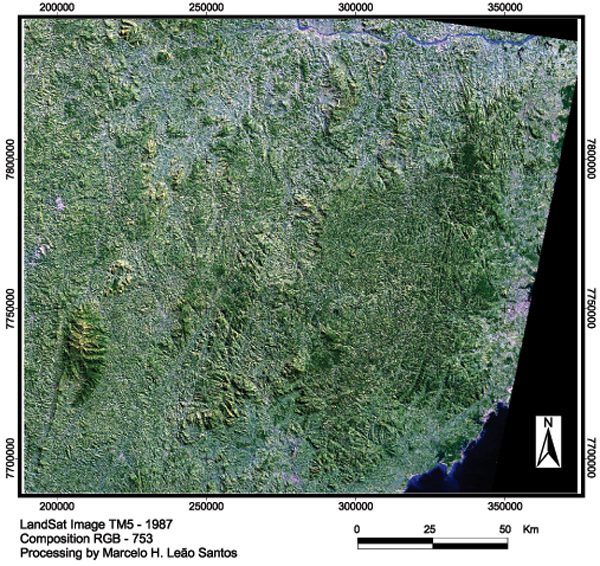

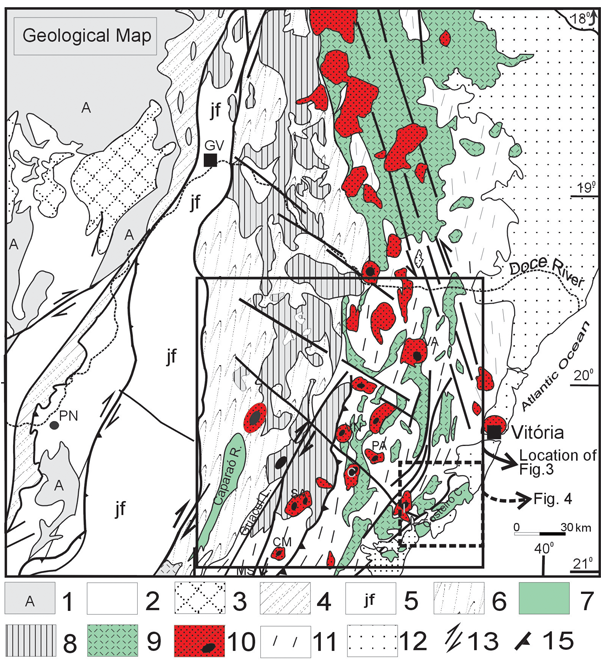

The Brazilian Atlantic coast, between southern Bahia and southern Espírito Santo States, consists of Neoproterozoic rocks from the Araçuaí Mobile Belt (Figure 1) [Pedrosa Soares and Wiedemann-Leonardos, 2000; Pedrosa Soares et al., 2001], with predominant N-S structural trends. South of 21 S the Araçuaí Mobile Belt inflects from N-S to NE-SW known as the Ribeira Belt [Almeida et al., 1973; Heilbron et al., 2000; Trouw et al., 2000]. The regional geological map on Figure 2 shows the main units of this segment and the northernmost parts of this gentle inflection displayed on the satellite image of Figure 3. This crustal section is part of Western Gondwana and continues in Africa as the West-Congo belt. A complex collision between the São Franscisco Craton, now in Brazil, and the Congo/Angolan Craton, now in Africa, drove the evolution of this belt.

Figure 2. Geological map of the southern Araçuaí-Ribeira Belt

Geological map of the southern Araçuaí-Ribeira Belt and cratonic surroundings, highlighting the Neoproterozoic units (modified from Pinto et al. 1998, Pedrosa Soares and Wiedemann-Leonardos, 2000; Wiedemann et al., 2002). 1 Achaean meta-sediments; 2 TTG complexes, with greenstone belts remnants and metasedimentary units; 3 Paleoproterozoic Borrachudos granitoid Suite; 4 Salinas Formation metavolcanic-sedimentary unit (correlated to Dom Silvério Group); 5 Juiz de Fora Complex; 6 Rio Doce Group; 7 granulite facies domain of Paraíba do Sul Complex, Late Paleoproterozoic and Mesoproterozoic; 8 and 9 Late Neoproterozoic to Cambrian metagranitoid suites: 8 I-type G1 suite (predominantly tonalite- grading into granodiorite- and granite- gneisses with minor amounts of diorite-, amphibole-gneisses, amphibolite and metagabbro); 9 S-type G2 and G3; 10 Late Cambrian to Ordovician granitoid suites: I-type G5 (black dots represent the mafic cores of plutons); 11 high-amphibolite facies domain of Paraíba do Sul Complex; 12 Phanerozoic Covers; 13 Magnetometric anomalies of the studied plutons; 14 oblique to strike-slip faults or ductile shear zones; 15 thrust and detachment faults or ductile shear zones. Cities: GV, Governador Valadares; PN, Ponte Nova. References in text.

The tectonic history of the Araçuaí-Ribeira belt is dominated by the amalgamation of a number of tectonic blocks from the closure of different segments of the Adamastor ocean (Pedrosa Soares et al., 2001; Brito Neves et al., 2000). The first record of subduction-related juvenile, intraoceanic, calc-alkaline volcano-plutonic arc was recognized in the southern region, in Rio de Janeiro State: the Rio Negro magmatic arc, at ~ 630 Ma. The accretion of this arc to the neighboring Transamazonian Juiz de Fora terrane (< 1700 Ma.) took place at ~ 600 Ma [Tupinambá et al., 2000]. Further north a well-defined gravimetric discontinuity, the Manhuaçu discontinuity, in Minas Gerais State, marks the boundary between the Transamazonian Juiz de Fora terrane and the Araçuaí Mobile Belt [Wiedemann et al., 2002]. The main oceanic plate convergence took place along the entire belt between ~ 600 - 580 Ma, forming a new intracontinental plutonic arc with strong crustal contribution (G1 granitoids, see below; Geiger, 1993; Brito Neves et al., 2000).

The post-Transamazonian supracrustal rock pile in the Araçuaí-Ribeira belt is known as Paraíba do Sul Complex (units 7 and 11 on Figure 2). U-Pb SHRIMP determinations on detritic zircon from this unit yielded 207Pb/206Pb age peaks varying from 2104 Ma, 774 Ma up to 631 19 Ma (Noce et al., 2004) which have been interpreted as the maximum and minimun source ages for the sediments. Rocks of this complex are subdivided into two units (Schobbenhaus et al., 1984): the Embú or Paraíba do Sul Complex sensu strictu (predominantly amphibolite facies - unit 11, in Figure 2) and the Costeiro Complex (predominantly granulite facies - unit 7). The Paraíba do Sul Complex consists mainly of a metasedimentary inhomogeneous package of partially migmatized banded gneisses, metamorphosed in the amphibolite to amphibolite-granulite facies transition. Metamorphic peak gave rise to the following paragenesis: garnet-biotite-plagioclase-microcline-quartz, garnet-cordierite-sillimanite-biotite-oligoclase/andesine-microcline, hypersthene-augite-andesine/labradorite and garnet-quartz-hornblende-biotite gneisses, biotite-garnet-cordierite-sillimanite-graphite gneiss, dolomitic and calcitic marbles and sillimanite-quartzite (Leonardos & Fyfe, 1974; Sluitner & Weber-Diefenbach, 1987; Féboli, 1993).

The Paraíba do Sul and Costeiro Complexes preserve rocks formed in two marine environments: 1) a proximal marine environment, probably a shallow shelf which received terrigenous siliciclastic material to produce common sandy rocks (graywacke gneisses and sillimanite-quartzite) interlayered with thick carbonatic layers; 2) a distal pelite-rich marine environment with minor carbonatic intercalations. The presence of graphite and high H2S-contents in the marbles point towards reducing conditions during the sedimentation process and confirm a shallow shelf marine environment (Geiger, 1993). Distal pelites gave rise to extensive kinzigitic gneisses with thin calc-silicate lenses (Ubu series). Scarce leptinite (a garnet-rich, biotite-poor leucocratic gneiss) and orthoamphibolite interlayered with kinzigitic gneiss indicate that alumina-rich shales accumulated in deeper marine environments with restricted mafic volcanic contribution (Pedrosa-Soares & Wiedemann-Leonardos 2000). Geochemical data from biotite- and biotite-amphibole-gneiss confirm that pelitic sediments and subgraywacke are the most probable protoliths (Geiger, 1993). Small igneous intrusions, consisting of metamorphosed gabbro, pyroxenite, diorite and biotite-andesine granitoids are also found in these terrains.

In summary, the Paraíba do Sul and Costeiro Complexes represent sedimentary marine sequences of Neoproterozoic age intruded during sedimentation (> 600 Ma) by small volumes of mostly basic magma and metamorphosed during the main collisional phase (from 600 to 575 Ma) to amphibolite/granulite facies. In the central part of Espírito Santo the roots of the Brasiliano Belt are exposed, revealing NE- trending, granulitic sequences, including kinzigites (coarse-grained sillimanite-cordierite-bearing granulites of the Paraiba do Sul Complex) interfingered with granitic-granodioritic gneisses (Delgado & Marques, 1993; Cunningham et al., 1998). The main collisional stage of the Brasiliano Araçuaí-Ribeira with the West-Congo Orogen, in this region, took place diachronously from ~600 Ma in the surroundings of the Caparaó Ridge, in the west (Sm-Nd whole-rock from granulites of the Caparaó, Fischel, 1998), to ~560 Ma, in the easternmost coastal region (U-Pb on zircons from granulites of the coastal region, Söllner et al., 2000). This compressive deformation episode caused crustal shortening of at least ~30 to 40% (Fritzer, 1991) and produced west-verging, moderately- to steeply-dipping thrusts (Pedrosa Soares et al., 2001). This process was accompanied by the development of metamorphic or migmatitic layering and tight to isoclinal folds (D1), refolded to form long-wavelength folds with upright to slightly west-verging axial planes and amplitudes up to 10 km (D2) such as the Caparaó ridge, a NE-SW-trending structure (the large hook-shaped mountain on the SE corner of Figure 3; Lammerer, 1987; Fritzer, 1991). Such folding is associated with contemporaneous stretching parallel to the horizontal plunging fold axes, indicating a prominent transpressive regime. At a late stage dextral, high-angle, oblique- to strike-slip shear zones truncated the previous folding. The Guaçuí lineament, east of the Caparaó ridge, is one of the most notable shear zones in this region (Figure 2).

This thick continental crust underwent different ultrametamorphic conditions in different regions of the belt. While the westernmost granulites from the Caparaó Ridge crystallized at 586 ± 2 Ma, under P-T conditions exceeding 10 kb and 800ºC (Seidensticker, 1990), along the Coastal region the formation of enderbitic granulites, under lower P-T conditions, was around 558 ± 2 Ma (Söllner et al, 2000).