Introduction

Molasse deposits are important because there is a considerable amount of tectonic detail that can be inferred from their deposition (Davis et al. 2004), for example erosion from different uplifted and exhumed parts of an orogeny can be deposited within a single molasse. There are a number of geologically significant molasse zones within the Himalaya mountain belt that have provided information on the evolution in both time and space of this mountain belt (e.g., Aitchison et al. 2002; Davis et al. 2004; Garzanti and Van Haver 1988; Rowley 1996; Sinclair et al. 2001): In the Siwalik Basin located in the Nepalese section of the Himalaya, there is a widespread molasse sequence along the foothills of the Himalaya (Najman et al. 2004); The Gangrinboche conglomerates bound the length of the Yarlung Tsangpo suture zone on the southern margin of the Lhasa terrane in the north of the Himalaya region (Aitchison et al. 2011); In south-central Tibet there is the Kailas conglomerate; The Bakiya Khola molasse in southeastern Nepal (Davis et al. 2004; Gansser 1980); and the Indus molasse lies fragmented along the Indus suture zone in NW of India.

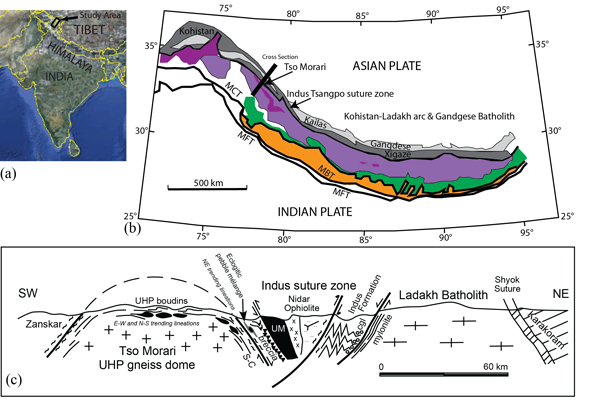

It is the Indus molasse on which this study is based (Fig. 1). These molasse are all laterally extensive but occur at different locations on the Himalaya belt.

Figure 1. Location of the study area.

(a) Map of NW India with the study area marked as rectangle (From: Google Earth); (b) Plan view of geological map of the Himalaya defining the major geological units. Our sample of the Indus Molasse comes from the Indus Tsangpo suture zone, which is dark grey in colour. Note: Kohistan-Ladakh arc and Gangdese batholith is light grey colour; Tso Morari/Tethyan metamorphic rocks in purple colour; orange is the lesser Himalayan Sequence; and dark green the Higher Himalayan Crystallines (modified from Guillot et al. 2008); (c) Schematic cross-section defining the major geological features in the NW Himalaya that include major structures such as the Zanskar, Tso Morari dome, Indus Formation and Ladakh Batholith. Note that location of the cross section is marked in (b) with heavy black line. The area of interest to this study is the northern section of the Indus Formation with a conglomerate zone immediately adjacent to the Ladakh Batholith (scale bar is given simply as a guide and overall distances are not to scale).

They are all laterally extensive along the length of the belt and in their location within the orogeny (perpendicular to the belt) from adjacent to the Main Front Thrust to the zones well behind the Indus Suture. The source of material in the molasse (e.g. pebbles) would thus be specific to the tectonic processes operating at that point in the orogeny at the time of their formation. The Indus Molasse is important due to its location adjacent to the Indus Suture and the tectonics relating to collision of India and Asia.

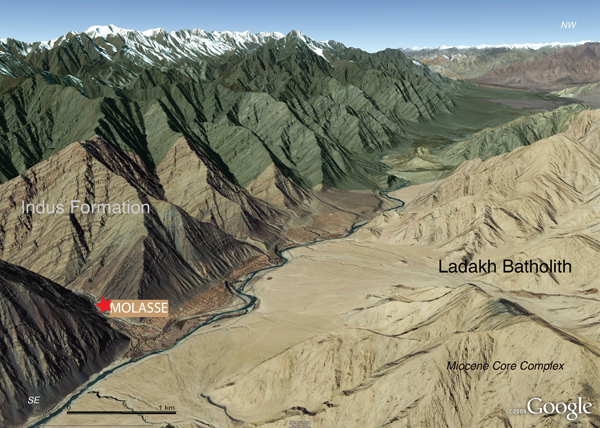

Figure 2. Google image of the Indus suture region.

The location of the pebble is marked by the red star on the boundary of the Indus Formation. The Indus River located diagonally along the centre of the map marks the boundary of the Indus Formation and the structurally underlying Ladakh Batholith on the right hand side of the image. The map is sourced from Google Earth: The pebble sample collection site (marked with a red star) is at 3,256 metres altitude at N: 33° 48’ 79.4”; E: 77° 48’ 63.8” ±14 metres.

Studies as early as the 1900s (e.g. by the Geological Survey of India) on the different molasse in the Himalaya shows an early recognition of their importance. These early studies provided observational information on the age and provenance of granitic pebbles in conglomerate zones (Auden 1933). The Himalayan molasse zones have provided a wealth of geological information, on tectonics (e.g., Searle et al. 1990, Harrison et al. 1993, Clift et al. 2002, Schlup et al. 2003), for geochemical and geochronological studies of provenance, erosion and drainage (e.g., Harrison et al. 1993, Clift et al. 2001), depositional rates, uplift characteristics, unroofing and cooling rates (Harrison et al. 1993), and the evolution of regional climate change (e.g., Harrison et al. 1993, Stern et al. 1997). Laterally extensive molasse units in the northern Himalaya region are a direct response to the orogen-scale tectonic processes caused by the India-Asia collision, recording aspects of its development (Aitchison et al. 2002). Similarly, the more southern extensive but fragmented Indus molasse also reflects regional-scale tectonics, extension and shortening events during the evolution of the mountain belt.

Thermochronolgical studies using 40Ar/39Ar geochronology can be used to calculate tectonic rates (e.g., unroofing, uplift, cooling) and chronostratigraphy that would otherwise be difficult to determine. This has been done at several locations on molasse in the Himalaya, for example in southeastern Nepal on the Bakiya Khola, where the molasse is laterally extensive and lies between the Main Boundary Thrust and the Main Frontal Thrust. In this case 40Ar/39Ar geochronology was undertaken to ascertain depositional ages that were then used to interpret the regional exhumation history (Harrison et al. 1993). In south-central Tibet Harrison et al. (1993, their figures 1, 2) have studied the Kailas conglomerate and provided 40Ar/39Ar cooling ages from which they have studied the rates and duration of uplift.

The Indus Molasse (equals the Kardong Formation in Thakur and Misra 1984) generally lies on the southern banks of the Indus River, in the NW Himalaya in Ladakh (Figure 1) and initially overlay the Indus Formation (prior to later folding and inversion, Figure 2). The northern boundary of the Indus Formation is irregularly bounded by this molasse that has accumulated as the result of erosion of the adjacent batholith and hence also includes pebbles from the batholith and leucogranite dyke swarms. The pebbles in the molasse at the study location also include ophiolitic material and perhaps pebbles from further afield (Figure 3a). We cannot be precise as to the exact location of their sources (cf Wu et al. 2007). What we can say is that the pebbles have been transported from an exhumed or exhuming and eroding igneous body and subsequently buried after their initial deposition, consolidated then folded during back thrusting over the Ladakh Batholith.

The southern margin of the Ladakh Batholith is occasionally bounded by S/SW-dipping ductile shear zones (e.g., N 33° 53’ 31.6”, E: 77° 45’ 34.2”). These structures may well define remnants of the carapace shear zone of a metamorphic core complex, although few data are currently available to support this hypothesis.

Figure 3. The Indus Formation with the suspected source of the pebble.

(a) Molasse with a variety of pebbles from different protoliths (image 700 mm wide); (b) Sedimentary layering in the Indus Formation with overprinting slatey cleavage in the shale and pull-aparts in the competent layer (image ~10 cm wide); (c) A representative pebble sourced from the Ladakh Batholith used in this study (pebble ~14 cm wide, ~21 cm long); (d) Ladakh Batholith with abundant leucogranites, located at the southern boundary of the batholith, the photograph has been taken near Chumathang, at the boundary of the Indus Suture zone (image ~800 m wide in foreground).

These shear zones appear to be extensional in character, with a regional south-directed normal-sense of movement. If this hypothesis is correct, parts of the Indus Formation are a molasse that formed as an apron at the margins of the Ladakh core complex, after its exhumation, once the lower plate was exposed. Later inversion resulted in back thrusting of the molasse over the Ladakh Batholith, during which episodes of recumbent then tight upright folds formed in the molasse. Pervasive axial plane fabrics developed during this later folding, overprinting the earlier formed structures. Here we report argon geochronology that allows constraint on the age of deposition of a pebble (Figure 3c) collected from a bed of the Indus molasse. The molasse at this location has subsequently been folded, and backthrust over the Ladakh Batholith.